UNRAVELING THE ORIGINS OF AN ANCIENT VILLAGE

For those of you who want to delve into the history and meaning of the circle, we will write about the Sacred Circle in much more detail here.

The discovery that I am going to tell you about is also, in part, the product of the collaborative synergies that social networks can produce. I will talk to you about the whole process of discovery because I find the process itself very interesting and because I believe that only by knowing the process is it possible to understand to what extent this strange thing is believable and makes sense. But the story is a bit long, so find a comfortable place to sit and read.

In January 2016, I was looking for possible traces of the old Roman road that crossed Peraleda from the ancient Roman town of Valparaíso to the city of Augustobriga. The route from Valparaíso is still easy to see until reaching Peraleda. The straight line then dissolves inside the maelstrom of our street layout and its successor may be a long street that winds a little through the town (Calle del Señor) and then turns towards the Tagus River. But it was by analyzing that layout as seen from the air that I discovered something that seemed surprising to me. Keep in mind that Peraleda’s street map is totally chaotic, without structure, a real labyrinth where outsiders get lost easily, since each street goes its own way and at its own pace, without the town centre square seeming able to attract the street network either. You can pass seven times bordering the square and still not see it! That is why I was very surprised to find a structure that did not seem chaotic, but rather circular.

To give something to talk about, I commented on Facebook that there was a large circle on the Peraleda street map, to see if anyone could find out what route it would take. After the general stupor (and intrigue), not even an hour passed when several people wrote with the correct answer. It is not that difficult, it is the only circular route that could be traced in Peraleda and as soon as you look for a circle... that is what it is, although none of us had noticed it before.

The next day I thought about it again, trying to figure out what that could mean or if it was just a coincidence. I took a map and superimposed a perfect circle. The circle coincided almost in the entire route (only with several houses that left the layout at two or three specific points) which seemed to confirm that it was not a coincidence. At first I wanted to assume that the circle would have been the old town square, the centre (since we know that the current square does not appear until the 16th century). But it was too big for a square! So I thought it might rather be the other way around, that this was the town, created inside a circular wall or palisade, which made much more sense. I even calculated how many families could live in that space, little corrals included, and I didn't get too few people, although I don't remember the number very well, I think up to about 500 people or so, good enough for a decent village at the time.

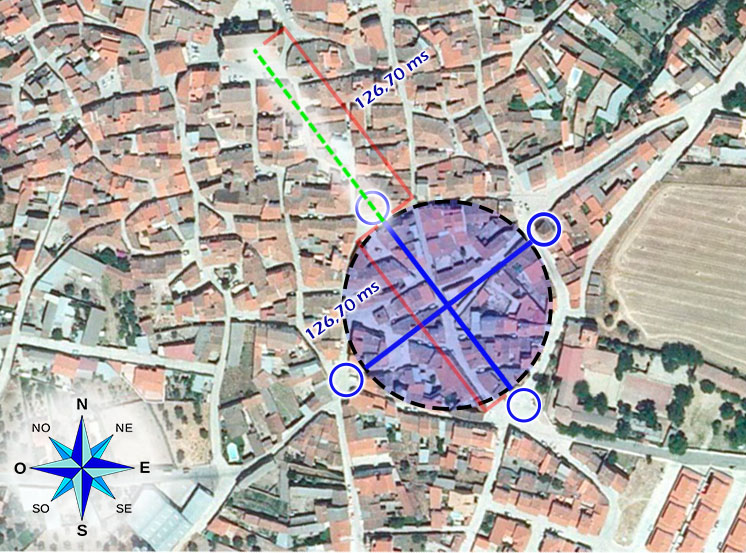

With this new perspective I assumed that if the layout had a Roman origin (because at that time I was still with the Roman mindset) it would have had its cardo and decumenum, the usual two streets making up a Greek cross and dividing the circle into four parts. In the street map there was no trace of an ancient Greek cross, but everything inside was quite chaotic (just like outside). No problem, it would be shacks or adobe houses in the "village of Asterix" without forming a street layout itself and without firmness to condition the layout of future streets either. But if there was some kind of fence, there had to be wall gates, and most likely there would be four, as is usual in Roman (and Celtic, etc.) enclosures, especially if they were not too large. I looked for signs of all four gates and they jumped out at me. Four small squares surrounded the perimeter of the circle. I joined the four small squares with lines and there the Greek cross appeared, still almost perfect. If the enclosure had four gates, as the town grew outside its walls, those gates would naturally become squares, since all the movement of people and animals that took place at the gates, together with the trading that was located in them, made new houses will be built around these spaces, not within them, the typical result in these cases. Therefore, the four small squares in the position of a Greek cross amply confirmed the hypothesis of the circle. Every step I took was reported on Facebook because the people who followed me from the beginning were enthusiastic about the subject.

But if Peraleda had been founded as a Roman village, or at least repopulated in the Middle Ages on the site of an ancient Roman or Celtic settlement, the logical thing would be for that Greek cross to be pointing to the four cardinal points, since ancient populations always did so. But what I then called "the ground cross of Peraleda” was not oriented towards the cardinal points, which was really strange. I started looking for information on the ground plans of Roman and Celtic populations to see if that was really as strange as I thought. I saw that the circular floor plan is more typical of the Celts, but the Romans were not unaware of it either (for example Lugo). And I saw that in the ancient world in general, in the few cases in which that "ground cross" is not oriented towards the cardinal points, it is because the orography of the terrain prevents it, or because there is a sacred place very close which becomes the natural point of orientation.

In our case, the orography could not be an impediment. So I wondered what sacred place there could be near Peraleda that would justify this orientation, and at first I couldn't think of any. But if it was a matter of orientation, the solution was simple: extend both sides of the cross (in this case more like an X) in the four directions and see where they point. Only one of the four directions seemed to point to a particular place, Northwest. The line that I traced on the ground for several kilometres (thanks to Google maps) brought me a double surprise, and again the confirmation, even more irrefutable) that this circle really existed and had a meaning. That extended line to the N.W. crossed the church of Peraleda through the middle, but even more surprisingly, it also passed through the very centre of an old church in ruins that was almost 5 km away, in the middle of the field. How did those people from the Middle Ages, from Rome or perhaps from long before, manage to align an entire town in the exact direction without deviating by several kilometres or even one meter? Because what we did know is that the circle, that part of the street layout, already existed in the Middle Ages, so it was built in earlier times.

And then an intuition led me to measure the length of those two ancient streets inside the circle, which gave me a diameter of 126.70 m. Again, I was astonished to verify that the distance from the door N.O. to the centre of Peraleda’s church was exactly 126.70 m. Exact. By building the church at that point the Greek cross in the circle was transformed into a Latin cross. And the Latin cross was like a great arrow pointing towards Santa Maria.

And that church in the middle of the field, the ruins of Santa María that we all knew very well and that nobody seemed to pay attention to, could it be a sacred place so important that an entire town turned to it (instead of turning to the north, like the pagans, or east, like normal Christians)? It seemed quite strange, there was only an old and rather small church there.

But the data seemed to indicate that this site at some point in the past must have been very important, so I began to think of different possibilities. The church of Santa María was built in the 14th century, and the circle of Peraleda had to be earlier, since Peraleda was founded (or repopulated) at the end of the s. XIII. The only solution was to think that this place was not sacred because the church of Santa María was built there, but that the church of Santa María was built there because it was a sacred place. Based on this hypothesis, I thought about what a sacred place would be like for Christians, for Romans, for Celts and even for prehistoric people (because Peraleda is in an important megalithic area and close to the renown Guadalperal Dolmen).

As I was still under the Roman mindset, I started asking questions about it to people on the internet. No one seemed to know anything about Santa María apart from the few things everybody knew about it. I asked if there were any Roman remains nearby. Indeed. Some sent me photos of Roman coins found in the area, others assured that there were tombs and inscriptions very close, and even remains of a Roman settlement had been found nearby. Close, but not “right there”, so what could have made that place sacred to those Romans who buried themselves nearby? It occurred to me that it was quite typical in Roman or Celtic antiquity to worship a goddess, spirit or nymph of the waters. These cults often arose in places where there were medicinal or thermal waters whose properties were considered to be caused by that deity. To verify, I asked if anyone knew of a nearby spring. Several told me that just a few meters away was the Borbollón fountain, a spring now covered by brambles and that hardly anyone knows about. I asked if they had heard of that water having any special characteristics, or legends or something. They told me that those were medicinal waters, that there used to be even a spa there and people from all over Spain came to heal, but that in the war they destroyed it and it was over. What more could you ask for? The source with medicinal waters was there, and that almost guarantees that the ancients had some kind of cult associated with the place, especially when it was shown that the Romans lived very close and therefore knew the site. The fountain was in the hollow, while at the top of the hill, to be clearly visible, there would have been some kind of altar or shrine perhaps, right where the ruins are today.

All this, as I said, published step by step and live on the Internet, caused quite a stir and there were people talking about it. That caused more bits of information to come to light. The study of ancient documents found months later shed even more light on the subject, and in summary, so as not to perpetuate ourselves, I will say that we learned that signs of Visigothic worship were found at the same point where Santa María is today, which seems to indicate that, already in times the Goths, a chapel or church was standing in that same place, later the Moors would have razed it to the ground and then it was rebuilt in the 14th century, which is the church in ruins we see right now.

The old patron saint of Peraleda and the surrounding towns was Our Lady of the Bell (“La Virgen de la Campana”, or “de la Mata”), who is said to have appeared in that place, which is why the church was built there. If the Visigoths had already built their church there, it is likely that reports from this apparition have its origin in Gothic times (a nearby spring called Wamba, the name of a Gothic king, reinforces that idea). But given the previous data, it is to be assumed that the Goths considered this site a sacred place because it was already considered sacred by their predecessors, the Romans, and perhaps they in turn inherited it from older peoples.

The importance of that place must have been such that even today the site of San Gregorio (as it is known today) is still considered an extraordinary site where all kinds of phenomena take place. People have seen (still see) apparitions of disturbing beings, lights, UFOs, voices, EVPs (electronic voice phenomenon) are recorded, sensitive people have strange sensations and perceptions, and those who are passionate about telluric energy lines affirm that this place is an important energetic knot where many lines of energy intersect.

“The Fourth Millennium”, a prime time TV program, has carried out an energy measurement in 2022 with surprising results. According to their data, in an area of only 100 m around the church they have obtained variations ranging from 21,000 nT (nanoteslas of electromagnetic energy) to 36,000 nT. Really a lot if we bear in mind that a value of 400 nT is considered very high. Besides, according to them, such a sudden and strong change could be enough to cause strange and powerful experiences in sensitive individuals, that is, the energy levels of the church and its surroundings are sufficient to make some people notice it and realize that this place is literally extraordinary. Not only in the church, but in a radius of 100 m around, which may explain why, even today, some people continue to have strange perceptions when driving along the road that passes next to it. This data confirms, once again, that the place has always been special and people have reacted in some way to it, and incidentally it shows that it is not necessary to enter the ruins to experience the unknown, it is enough to be close by, for example in the curve of the former road, where you can park, since the ruins are fenced and it is private property (if you don't experience anything there, you won't experience it inside either).

Be that as it may, even today the site of the ruins has not ceased to be considered a kind of door to another dimension, in addition to its traditional sacred value for Christians (the place where the Virgin appeared and where the first parish church for all the area was). Although we all knew some things, the stir of the subject made many more details come to light and we realized that the place was really much more important than any of us had fathomed until then.

But even in Christian times, it turns out that the place was much more sacred than the current ruins seem to suggest. Fray Alonso Fernández wrote in his chronicle of the year 1180 that Our Lady of La Mata was one of the most important devotions in the diocese, before the discovery of the image of Guadalupe eclipsed all of them and concentrated there all the Marian pilgrimages which used to go to these other sanctuaries. So we can see that the importance of the place went beyond the areat.

Later, an ancient document revealed yet another very curious and unknown fact. The original name of that Virgin was not Our Lady of the Bell, but Our Lady Santa María of Compostela, an obvious reference to Santiago de Compostella, the shrine of St James the Apostle in the north-west of Spain. There were only a few virgins named like that in all of Spain, and they were all right on the Camino de Santiago (the Way of St James, the pilgrims’ path to his shrine), that is why they were called “of Compostela”. Did our Virgin have a relationship with Santiago? Peraleda’s church is indeed dedicated to St James. Looking at the medieval pilgrimage routes, nothing mentions a route passing through Peraleda, though that’s not strange, since there is very little information about that. But in several nearby towns there is a church dedicated to St James, even a nearby town, today disappeared, was called Puebla de Santiago (village of St James). I decided to unite those churches with a line, and that line pointed towards the centre of Spain. So I looked for all the present or past churches, convents or hospitals that were dedicated to St James in the entire area between the range of mountains to the north and to the south of Peraleda. The result is conclusive: two lines starting from the outskirts of Madrid headed west, one the north of the Tagus and the other along the south banks of the river. And both lines met in Peraleda! The next church is already in the mountains, in La Vera (Losar), and the next in Plasencia, so there had to be two pilgrimage routes that headed from the centre of the peninsula (thus avoiding dangerous roads crossing the mountains) towards Peraleda to reach Santa María (of Compostela), and from there they went up to Plasencia to join the west branch of St James’ Way (La Ruta de La Plata), comfortable and paved. It made a lot of sense.

With this, it was twice the times that Santa María (and Peraleda along with it) was shown associated with a pilgrimage route: a pilgrimage to Santiago and a pilgrimage to Our Lady of the Bell. It is also possible that even before Christian times this sacred place had also been a centre of pilgrimages; because if it was so important, many would travel to benefit from it. With a maybe pagan and a largely confirmed Christian pilgrimages, the circle of Peraleda now acquired a new context. Peraleda is next to Alarza Ford, which is one of the few places (and one of the 2 or 3 best) where you could cross the River Tagus and therefore travel from the south to the north of the peninsula through its western half. If Santa María was the focus of pilgrimage routes, those routes from the west and south had to converge in Peraleda before heading northwest to Santa María, as we have seen with the two routes to Santiago (St James shire). Peraleda would then be a place of confluence where pilgrims from different places gathered before undertaking the last 5km stretch towards their final destination.

The circle of Peraleda was thus a pilgrim reception centre (a bit like today’s El Monte del Gozo, some km before arriving in Santiago). It was at the same time a gathering point and the place to get properly ready (purified) before getting to the destination. In that context, what meaning could an urban circle like ours have?

This is where we ran out of data and the only way forward was to study how pilgrimages worked both in the Middle Ages and in cultures prior to Christianity, and also investigate what function or meaning the architectural circles had in those towns. There aren't too many instances of circles associated with pilgrimages, so that simplified the task. The interesting thing is that the common or frequent traits that we have discovered, although most examples are found in Europe, also appear in some ancient cultures in other parts of the world.

So on the one hand we have the circle working as a condenser of energy. Within the circle the energy condenses, but it also radiates. Often that energy comes from the earth or the sky, or from some object or event inside it, but in some cases that energy is collected from another nearby place, and the circle has the function of capturing that energy. That seems to be clearly the case of the Circle in Peraleda, since the sacred place was outside, in Santa María, and pointing towards it would be a way of capturing the energy of that place, like a receiving antenna, so that the people who lived or were temporarily inside that circle were blessed with the sacredness of the other place. In that case the energy of the wheel is condensed in its centre, and from there, it radiates throughout the circle. From a Christian point of view it would be like attracting the protection of Our Lady for the whole town, and from a pagan point of view it would be like attracting the energy of that place (or the spirit or deity) to distribute it throughout the town.

On the other hand, we have seen the function of the circle within a pilgrimage route, which also tends to be not at the final destination but before the final destination. The circular labyrinths of the French cathedrals where there were pilgrimages immediately come to mind. They were at the entrance of the cathedral and the pilgrim who arrived, before reaching the tomb or relic sought, had to enter that circle and walk the path inside it in an act that they considered purification. But that characteristic is found in some other places, Christian, Celtic and even from other cultures (Buddhist, Muslim, etc.). The idea is that shortly before reaching the destination, the pilgrim has to purify himself, and when we find a circle in that context it is because purification takes place in that circle.

In those cases we sometimes find the labyrinth, as in French cathedrals, where pilgrims walk along a twisting path within the circle. But in other cases the circle is much larger and then the circle itself is the way to go. In the few cases like this which we have found data about (because of a living tradition or reports from ancient traditions are still preserved), it is frequent for the pilgrim to purify themself by going around the circle three times (the number 3 has always been associated with the sacred in very different civilizations). In addition, the turns are usually clockwise, why? Because the sacred is somehow associated with the sun, and in the northern hemisphere the sun moves through the sky (half a turn) clockwise (it is more clearly seen in winter), so it is not strange to find the three solar turns in Christian pilgrimages from Europe, indigenous people from America, Buddhists or Celts, for example. This phenomenon falls within the religious ritual that in Sanskrit is called pradaksina and in English or French circumambulation (from the Latin circum ambulatus, to walk around the circle).

Following these general schemes we have reconstructed what the function of the Sacred Circle of Peraleda could be. On the one hand, it would be a settlement inside a circular wall oriented to the point where Santa María is today and destined to collect, for its inhabitants, the blessing-protection of that sacred place. On the other hand, it would be the last stage of the pilgrimage routes (pagan first and later Christian) that came from the east and south, where the pilgrims purified themselves before reaching their final destination (already a little over an hour away). That purification rite would consist of walking around the perimeter of the circle three times in a clockwise direction, and then probably standing right in the centre and getting purified and/or charged with sacred energy before heading to the final destination. We are not so sure about this last step because we find a bit of everything, but what is clear is that, if someone believes that the circle is an energy condenser of some kind (sacred, telluric...), the point of the circle where the energy is concentrated with the most intensity has to be its centre, so whoever is looking for energy, that is the point where he should end.

If the said measurements of “The Fourth Millennium” are correct, we can consider scientifically proved that there is energy there, and in abundance, so just as modern man perceives it in some way and it has different kinds of effects on them, likewise ancient man (in fact of all times) must have felt those effects too and must have looked for a way to channel that energy in their favour. If for today's man these things are anecdotal or directly ignored, for ancient man these things were of great importance and they could not let it slip away like it was nothing. The Circle of Peraleda seems to be his response to that opportunity that was offered to them.

From there, Raíces de Peralêda cultural association decided to add this discovery to our list of things we can offer visitors. We have been preparing everything for months and now we are finally ready to surprise the visitor with an experience that will not leave them indifferent, and which can even transform those who are sensitive enough to perceive these energies that are still active today as always. Rebuilding the circle has been a simple task, because it is practically intact, so our job has been to signpost the route and offer information.

Starting in front of the town hall, in the town’s square (la plaza), some arrows on the ground indicate the direction towards the Sacred Circle, guiding the visitor through Peraleda’s labyrinth to the beginning of the Circle. There is an information panel there where visitors are informed of what it is, what it means and how they can relive the ancient or ancestral pilgrimage. Another batch of arrows on the ground guide the modern pilgrim around the Circle, and once the three turns have been completed, a couple more arrows will guide them to the centre of the Circle, where they will find a round plaque on the ground with the ancient legend “Venite et Implemini” (come and be replenished). Those most sensitive to these energies will be able to stand on the plaque and feel how their being is recharged and purified, just as multitudes of pilgrims must have done before him over centuries, probably millennia.

The less sensitive will be able to stand on the plate and take a selfie of their feet.

It is therefore an experience to live, to feel, and we are sure that it will impact some people, just as it is the case in other famous places considered sacred or energetic points. The eclectic past that this place had makes its new pilgrimage just as good for the Christian who wants to honour the Virgin as for those who are simply looking for energies or different states of consciousness. Also for those who today search among the stones of the neighbouring dolmen (almost always under water and therefore out of range) that energy that connects them with who knows what. They all have a place, because the experience is internal, although the energy, so it seems, is real and is out there. And those who are not looking for energy will find an original and different experience that will give them an excuse to enjoy other attractions that Peraleda and the area have to offer.

For us, this has meant getting to know our history better, discovering a new meaning to our home, and having one more element (and not a small one) to share with visitors, as a new resource that helps us prosper and ensure that these streets that we have spent centuries inhabiting may not soon be left empty and dead.

Escrito por Angel Castaño